|

<Back>

CONTINUING CRACKDOWN IN

INNER MONGOLIA

March 20, 1992

An Asia Watch Report

A Division of Human Rights Watch

Human Rights Watch Human Rights Watch

485

Fifth Ave., 3rd Floor 1522 K Street, NW

New

York, NY 10017 Washington, DC 20005

(212)972-8400 ( 202)371-6592

Fax:(212)972-0905 Fax:(202)371-0124

© 1991 by Human Rights Watch

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 1-56432-059-6

THE ASIA WATCH COMMITTEE

The Asia Watch Committee was

established in 1985 to monitor and promote in Asia observance

of internationally recognized human rights. The chair is Jack

Greenberg and the vice-chairs arc Harriet Rabb and Orville

Schell. Sidney Jones is Executive Director. Mike Jendrzcjczyk

is Washington Director. Patricia Gossman and Robin Munro are

Research Associates. Jcannine Guthrie and Vicki Shu are

Associates. Dinah PoKempner and Mickey Spiegel is a

Consultant.

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH

Human Rights Watch is composed of five Watch Committees:

Africa Watch, Americas Watch, Asia Watch, Helsinki Watch and

Middle East Watch.

Executive

Committee

Robert L. Bernstein, Chair; Adrian DeWind, Vice-Chair; Roland

Algrant. Lisa Anderson, Peter Bell, Alice Brown, William

Carmichael, Dorothy Cullman, Irene Diamond, Jonathan

Fanton,Jack Greenberg, Alice H. Henkin, Stephen L. Kass,

Marina P. Kaufman, Jeri Laber, Arych Neier, Bruce Rabb,

Harriet Rabb, Kenneth Roth, Orville Schell, Gary Sick, Robert

Wedgeworth.

Staff

Aryeh Neier, Executive Director; Kenneth Roth, Deputy

Director; Holly Burkhalter, Washington Director; Ellen Lutz,

California Director; Susan Osnos, Press Director; Jemera Rone,

Counsel; Stephanie Steele, Operations Director; Dorothy Q.

Thomas, Women's Rights Project Director; Joanna Weschler,

Prison Project Director.

Executive

Directors

Africa Watch Americas Watch Asia Watch

Rakiya Omaar Juan Mendei Sidney Jones

Helsinki Watch Middle East Watch Fund for Free

Expression

Jeri

Laber Andrew Whitley Gara LaMarche

Contents

Introduction

................................................................................................................

1

Update on the 1991 crackdown and new cases of concern

....................... ................. 2

Why

the Crackdown?

.................................................................................................

5

Appendices

................................................................................................................

8

I.

Report on Human Rights Conditions in Inner Mongolia (II)

................... 8

II.

On Further Stabilizing the Minority Areas in the Frontier

Regions:

the

Situation and our Views

...............................................................

14

III.

Circular on Matters Needing Attention of Citizens in Their

Contacts with Foreign Nationals in the Open

Cities and Areas of Our Region

......................................................... 19

IV.

Urgent Circular on the Management and Reception

of

Uninvited Groups or Groups to be Invited but Already

Arriving from [Outer] Mongolia

......................................................... 22

V.

Previously Reported Cases of Concern

............................................. 24

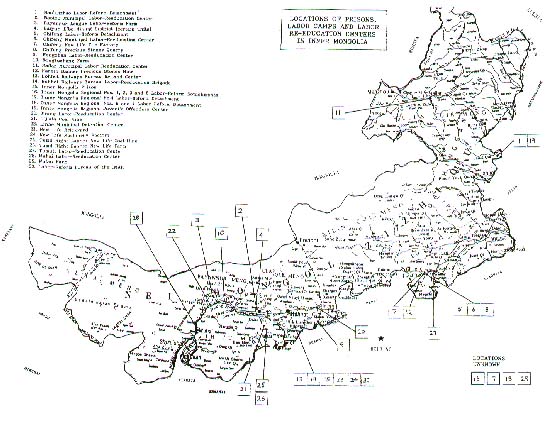

VI.

Labor Camps, Prisons and other Detention

Units in Inner Mongolia

.....................................................................

26

Errata for Crackdown in

Inner Mongolia

................................................................

34

1.

Bao'an zhao Labor-Reform Detachment

2.

Baotou Municipal Labor-Reeducation Center

3.

Bayannur League Labor-Reform Farm

4.

Baiyun E'bo Mining District (certain units)

5.

Chifeng Labor-Reform Detachment

6.

Chifeng Municipal Labor-Reeducation Center

7.

Chifeng New Life Tile Factory

8.

Chifeng Precious Stones Quarry

9.

Fengzhen Labor-Reeducation Center

10.

Dongtucheng Farm

11.

Hailar Municipal Labor-Reeducation Center

12.

Harqin Banner Precioue Stones Mine

13.

Hohhot Railways Bureau Remand Center

14.

Hohhot Railways Bureau Labor-Reeducation

Brigade

15.

Inner Mongolia Prison

16.

Inner Mongolia Regional Nos. 1, 2, 3 and 5

Labor-Reform Detachments

17.

Inner Mongolia Regional No.4 Labor-Reform

Detachment

18.

Inner Mongolia Regional Nos.6 and 7

Labor-Reform Detachment

19.

Inner Mongolia Regional Juvenile Offenders

Center

20.

Jining Labor-Reeducation Center

21.

LiJiata Coal Mine

22.

Linhe Municipal Detention Center

23.

New Life Brickyard

24.

New Life Machinery Factory

25.

Tumd Right Banner New Life Coal Mine

26.

Tumd Right Banner New Life Farm

27.

Tumuji Labor-Reeducation Center

28.

Wuhai Labor-Reeducation Center

29.

Wulan Farm

30.

Labor-Reform Bureau of the IMAR

Introduction

In

early May 1991, the Chinese authorities launched a secret

campaign of repression against ethnic Mongolian intellectuals

in China's third largest administrative area, the Inner

Mongolian Autonomous Region (IMAR). In July 1991, Asia Watch

published a preliminary report on the repression, entitled

Crackdown in Inner Mongolia. That report included our

translation of Document No.13, a top-secret Communist

Party directive explaining and ordering the crackdown; the

text of an urgent appeal issued from the IMAR in late May by

an underground group called the Inner Mongolian League for

the Defense of Human Rights (Neimenggu Baowei Renquan

Tongmeng); and, byway of background, extracts from a secret

Party document of August 1981 which assessed the appalling

damage and suffering inflicted upon ethnic Mongolians in the

region during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76).

The

present report provides an update on the ongoing repression

against peaceful dissenters in Inner Mongolia over the past

six months and summarizes other related developments in the

region. It also contains the text of a second appeal document

issued by the Mongolian underground group mentioned above,

together with further confidential documents issued by the

Party in 1990 and 1991 detailing its policies toward ethnic

minorities and setting forth restrictions on access between

inhabitants of the IMAR and foreigners - in particular,

Mongolians from the neighboring Mongolian People's Republic [MPR].

In addition, the report lists details of all the known prisons

and forced labor camps in the IMAR.

The

campaign of repression began in May 1991 with the crushing of

two small private study groups - called the IhJu League

National Culture Society and the Bayannur League

National Modernization Society - which had been formed

over the previous year or so by like-minded Mongolian

intellectuals and Party cadres in an attempt to regenerate the

region's long- suppressed Mongolian ethnic and cultural

identity.1 The groups operated openly and with the

full knowledge of senior local officials and had even applied

for legal registration. According to Document No.13,

issued on May 11, 1991, however, the two groups “used the

discussion of ‘national culture’ and ‘national modernization’.

. . to oppose the leadership of the Communist Party and the

socialist system, and to incite a national split and undermine

the unification of the motherland.”

The

first arrests came swiftly. On the night of May 15, 1991, two

young Mongolians named Huchuntegus and Wang Manglai,2

both leaders of the Ih Ju League National Culture Society

and employees of the league's Bureau of Education, were seized

by security agents at their homes in Dongsheng, the local

capital, and 26 other key members of the society were placed

under house arrest.3 At the time, nothing was known

concerning the fate of those active in the group based in

Bayannur League, a more remote pan of the IMAR and one largely

closed to foreigners.4 Document No.13 had

characterized this group as being more politically radical

than the Ih Ju group, however, and it seemed likely that

particularly stern measures would be taken against its

organizers. Besides these ethnic Mongolian activists, a number

of student and worker demonstrators are also known to have

been arrested in Inner Mongolia after the June 1989 nationwide

crackdown on the pro-democracy movement. Those still believed

to be imprisoned there include Tasu, Wang Shufeng and Qian

Shitun, all leaders or members of the Autonomous Federation

of Students from Outside Beijing; Bao Huilin, Cai Shi, Wen

Lihua, Yang Xudong and Zhang Lishan, leaders of the Hohhot

Workers Autonomous Federation; and Zhao Guoliang. a

self-employed garment vendor. (See Appendix V for details.)

Update on the 1991 crackdown and new cases

of concern

On

June 30, 1991, a second appeal statement, bearing the

signature of an ethnicMongolian named Burghud (Bu-er-gu-te

in Chinese) was issued by the underground Inner

Mongolian League for the Defense of Human Rights (see

below for full text). Nothing is known about Burghud, and the

name may well be pseudonymous. Burghud’s appeal statement

summarized as follows the severe crackdown operation

undertaken by the regional security authorities in the wake of

the May 1991 arrests:

After the events of IhJu and Bayannur

Leagues, Wang Qun [Party Secretary of the IMAR] became

convinced that there are also "illegal organizations" and

"national splittist elements" in the other six leagues and

four municipalities directly under the autonomous region.

Therefore, at the same time as he sent public security and

state security agents to IhJu and Bayannur Leagues, he also

deployed secret police in Hohhot, the capital city of Inner

Mongolia, and the other leagues and municipalities....They are

acting in the utmost secrecy...

In

order to step up the repression, the Beijing authorities have

transferred large numbers of experienced public security and

state security agents from Beijing, Hebei and Shanxi to Inner

Mongolia...More and more people are being secretly questioned,

watched and followed. An increasing number of students,

teachers, cadres and workers are becoming suspects. Some

high-ranking ethnic Mongolian officials have also become

targets of investigation. Panic and unease are spreading.

According to sources, the authorities have

expanded their investigations to ethnic Mongolian college

students studying in universities in the Xinjiang Uighur

Autonomous region and in Gansu, Liaoning and Henan Provinces.

These students are or soon will be facing persecution.5

On

specific cases, the appeal statement reported that one

Bayantogtokh,6 a secondary school teacher and

leader of the Bayannur League National Modernization

Society, had some time earlier been seized by the

authorities, together with seven other key members of the

group, and taken to Linhe, the league's capital. Bayantogtokh

was said to have later been secretly tried (length of

unknown), and there was no further information on the fate of

his seven colleagues.

Concerning the IhJu League National Culture Society,

the statement reported that Wang Manglai, 30, and Huchuntegus,

36, had been placed under so-called “shelter and

investigation” (an unregulated form of police administrative

detention which can mean almost indefinite incarceration

without trial), and transferred to a secret prison in Hohhot,

the regional capital. The prison was said to be administered

by Section 5 of the IMAR Public Security Bureau and to be

designed to hold major political prisoners, Huchuntegus1 wife,

Dabushlatu, was reportedly being subjected to constant

official harassment and persecution, and neither she nor Wang

Manglai’s wife had been informed of their husbands’ place of

detention or allowed to visit them.

Burghud added that the 26 members of the group earlier placed

under house arrest had since been repeatedly interrogated by

the police and subjected to insults, intimidation and physical

abuse, and that eight of them - including one Sechenbayar,

a researcher at the In Ju League's Ghengis Khan Research

Center - would soon be placed under formal arrest. A

“mandatory study campaign” had been launched throughout the

league, moreover, in the aim of forcing the local population

to “repudiate and expose” the group’s alleged “crimes of

national splittism and bourgeois liberalization.”

Another recent case of great concern is that of Ulan Chovo,

37, reportedly a professor of history at the University of

Inner Mongolia.7 Asia Waich has received three

separate reports indicating that Ulan Chovo was arrested

sometime after the May 1991 crackdown (probably on July 11)

and charged with passing confidential documents to foreigners.

According to one report, he had been secretly tape-recorded

and photographed doing so. According to another report, which

came direct from ethnic Mongolian sources in Hohhot, Ulan

Chovo was recently tried in secret and sentenced to five

years' imprisonment.

The

documents in question were almost certainly the first appeal

statement by the Inner Mongolian league for the Defense of

Human Rights and the IMAR Party Committee’s Document

No.13. In September 1991, a journalist named Andrew Higgins,

Beijing-based correspondent for the British Independent

newspaper, was detained and searched at a Chinese airport and

found to be in possession of these documents, the contents of

which he had filed a report on to his newspaper some days

earlier. Higgins was subsequently expelled from the country.8

As noted above, Asia Watch, which had obtained the documents

by an entirely separate channel, in July 1991 published both

documents in full translation. While neither Higgins nor Asia

Watch obtained the documents from Ulan Chovo, it is clear that

the Chinese authorities regarded the publication abroad of

these documents as being a major embarrassment, and it is

likely that no efforts were spared - including even the use of

physical torture - to track down the source of the leak and

obtain a confession. A photograph of Ulan Chovo, obtained from

dissident Inner Mongolian sources living abroad, is included

below.

Another case cited in the June 1991 appeal by the Inner

Mongolian League for the Defense of Human Rights concerns a

journalism sophomore named Zhang Haiquan, an ethnic

Mongolian, who was arrested shortly after June 4, 1991 (the

second anniversary of the 1989 Beijing massacre) in connection

with “reactionary slogans” - including “Long live democracy”

and “Long live the Guomindang” - which had appeared on a

classroom blackboard at the University of Inner Mongolia.

Nothing further has since been heard of Zhang Haiquan.

Other ethnic Mongolian dissidents known to be imprisoned in

Inner Mongolia on account of their peaceful political beliefs

include a man named Bater, 35, formerly an official in

the government planning commission of Xilin Gol League, and

Bao Hongguang, also 35, an engineer. Both men were leaders

of a large-scale student protest movement against Han

domination of the IMAR that had rocked the region in 1981. In

the summer of 1987, following official persecution, Bao and

Bater escaped across the border to the Mongolian People’s

Republic and sought political asylum there, but were

subsequently extradited back to China and each sentenced to

eight years’ imprisonment. Their current place and conditions

of detention are not known.

In

early 1992, scattered evidence of major incidents of social

unrest having occurred in recent months began to trickle out

from Inner Mongolia. According to the February 1992 issue of

the Hong Kong magazine Dongxiang (“Trends”), for example,

large-scale protest demonstrations in support of Inner

Mongolian independence took place in no less than six key

cities in the region -Jining, Hailar, Tongliao. Xilinhot,

Linhe and Erenhot - between November 1991 and January 1992.

According to the report, more than 20 people were injured in

Tongliao on November 6 when demonstrating herdsmen exchanged

gunfire with PLA troops sent in to quell the protest.9

In early February 1992, Asia Watch received a broadly

similar report from a Western traveller who had returned from

the region in late January. According to the source, large and

sometimes violent protest demonstrations had occurred in

Bailar, Jining, Erenhot and Xilinhot in recent weeks. Calls

for reunification with the MPR had been raised and a number of

workers and others had been arrested.

Why the Crackdown?

The

continuing crackdown by Beijing against ethnic and political

dissent in the IMAR reflects the central authorities' intense

current concern over two separate but related issues:

incipient nationalist tendencies among the country's ethnic

minorities, and the broader nationwide trend toward democracy

which was abruptly suppressed on June 4, 1989. Concerning the

two Mongolian study groups in Ih Ju and Bayannur Leagues, the

Party's top-secret Document No.13 specifically noted:

“It is clear that our struggle against these illegal

organizations is in fact the continuation of our struggle

against bourgeois liberalism. It is the concrete expression of

the struggle between subversion and anti-subversion,

infiltration and anti-infiltration, peaceful evolution and

anti-peaceful evolution in our region.”

More

recently, Wang Qun, Party secretary of the IMAR, has denounced

alleged Western interference in the region and urged Inner

Mongolians to "build up a great wall of steel against

‘peaceful evolution.’” According to Wang, “At present, hostile

international forces have gone all out to carry out ‘peaceful

evolution’ against China. Their habitual practices include

imposing economic sanctions, stirring up trouble among the

masses, and engaging in sabotage under the guise of

‘nationality,’ ‘religion,’ ‘democracy,’ and ‘human rights.’”10

The

real threat to BeiJing’s power in the IMAR seems, however, to

lie much closer to home. As Party General-Secretary Jiang

Zemin pointed out, in a confidential keynote speech of March

1990 entitled “On Further Stabilizing the Minority Areas in

the Frontier Regions” (see below for full text):

The "Democratic League" and other opposition groups in the

Mongolian People's Republic [MPR] claim to have the support of

their "Mongolian brothers and sisters" within China's borders.

There are some in the MPR who are vainly trying to establish a

so-called Greater Mongolian State that would include the

Buryat (ethnic Mongolian) Autonomous Republic of the Soviet

Union and also our Inner Mongolia. The slogans used by the

reactionary elements within and outside both Inner Mongolia

and Xinjiang are extremely similar -for example, “No nuclear

testing,” “Against the plunder of our resources” and “Drive

away the outsiders.”

For

several days in October 1991, a group of Mongolian students

(apparently all from the MPR) staged a rare sit-in protest in

sub-zero temperatures outside the Chinese Embassy in Ulan

Bator calling for an end to the repression in Inner Mongolia.

The group handed embassy officials a letter to Premier Li Peng

calling for the release of six imprisoned Inner Mongolian

dissidents and two of China's most famous pro-democracy

figures. “We want the release of the eight prisoners, an end

to Chinese human rights abuses in Inner Mongolia and a stop to

the Chinese policy of assimilating our Inner Mongolian

brothers,” said one of the protestors, a student at Mongolian

State University named Dashdorj Rensentavhai. A notice board

set up by the students carried photographs of them burning the

Chinese flag and a cloth effigy of a Chinese policeman, and

their banner read “Stop Communist Repression in Inner

Mongolia.”11

The charge of separatism and attempting “to

split the motherland” has long been leveled by Beijing against

the pro-independence movement in Tibet. The IMAR, however, is

effectively pan of a divided nation, and this adds a new and

potentially explosive element to the Inner Mongolian question

(and also that of Xinjiang) that is not found in the case of

Tibet. The arrival in 1990 of democratic reforms and the

establishment of a multi-party system in the neighbouring

Mongolian People’s Republic (now renamed the State of

Mongolia) seem clearly to have intensified the sense of

discontentment felt by many ethnic Inner Mongolians within the

context of this divided nationhood.12 As the documents

presented here and in Asia Watch's previous report on Inner

Mongolia indicate, moreover, sections of the emergent

dissident movement there do appear to incline, albeit quite

peacefully, toward the idea of some kind of eventual Mongolian

reunification.

What

is certain is that recent world events, starting with the

Romanian revolution and culminating in the reconstitution of

the former Soviet Asian republics as independent states, have

served to raise the Chinese leadership’s anxieties about such

matters to virtual fever pitch. In the speech cited above,

Jiang Zemin went so far as to warn darkly: “Some people are

vainly searching for a ‘Timisoara’ in China’s ethnic minority

regions.” Given Beijing's current siege mentality on the issue

of political opposition, international scrutiny of the human

rights situation in Inner Mongolia and other ethnic-minority

regions of the People’s Republic is henceforth likely to

become ever more urgent and necessary.

In

the meantime, Asia Watch calls upon the Chinese Government

immediately and unconditionally to release Huchuntegus,

Wang Manglai, Bayantogtokh, Bater, Bao Hongguang, Ulan

Chovo, Wang Shufeng, Qian Shitun, Bao Huilin, Cai Shi, Wen

Uhua, Yang Xudong, Zhang Lishan, Zhang Haiquan, Tasu, Zhao

Guoliang and all others currently imprisoned in the IMAR

on account of their peaceful political beliefs and activities.

A list of known political detainees in Mongolia is attached as

Appendix V.

Appendix

I

Report on Human Rights Conditions in Inner Mongolia (II)

By

Burghud of the

Inner Mongolian League for the Defense of Human Rights

June

30, 1991

According to disclosures by a public security agent of Inner

Mongolia, after the illegal arrests of Huchuntegus and Wang

Manglai [leaders of the outlawed “Ih Ju League National

Culture Society” ] on May 15 on the pretext of taking them in

for “shelter and investigation” (shourong shencha),

they were secretly sent under escort from the Municipality of

Dongsheng in Ih Ju League to Baotou. Recently, they were moved

again, this time to Hohhot, and are being held in a secret

Jail administered by Section 5 of the Public Security Bureau

of Inner Mongolia. That jail is used by the authorities to

hold the “most dangerous” political prisoners. Huchuntegus and

Wang Manglai have been held incommunicado ever since they were

arrested. Their families are not allowed to visit them. They

do not even know where their loved ones are being held.

Dabushlatu, wife of Huchuntegus, is an accountant working for

the Nationalities Bazaar in the Municipality of Dongsheng. She

is 32, and they have a boy of six. She has constantly been

harassed, watched and followed since her husband's arrest. She

has been illegally questioned many times by the police, and

her personal freedom is being restricted. The authorities

forbade her to travel and ordered the management of the bazaar

to report her words and deeds regularly to the police.

Instigated by the authorities, some people even directly

threatened Dabushlatu's personal safety. On one occasion, when

she was talking in the Mongolian language with someone at her

place of work, she was upbraided and told to shut up by an

ethnic Han colleague. Dabushlatu has lost touch with her

husband and is being subjected to all kinds of pressure. She

is being spiritually tortured and she has no idea when her

travail will end.

Wang

Manglai's wife is an editor working for the local television

station in Ih Ju League. They have two children; the younger

one is still in its infancy. Her husband’s arrest by the

police deeply traumatized her. She cannot even find a nanny to

look after her children so that she could go to work. She has

spent the month and a half in agony, fear and helplessness.

She only wishes to know where her husband is being held and

when she could see him, if only for a moment. But no one knows

how long Huchuntegus and Wang Manglai will be kept in prison.

As

for the fate of Huchuntegus and Wang Manglai, people have

fears that an open and fair trial is almost out of the

question. This is because the authorities really cannot

produce any evidence to show that the defendants violated any

Chinese laws that are in force. According to document number

13 of 1991 issued by the Office of Inner Mongolia Communist

Party Committee, their "crime" consists primarily of the

following three points:

1.

having founded an illegal organization;

2.

having worked to split the nationalities and propagated

bourgeois-liberal ideas;

3.

having illegally printed and distributed a political tract

published in the Mongolian

People’s Republic.

But

none of these three charges are tenable.

First, Huchuntegus and Wang Manglai initiated the founding of

the Ih Ju League National Cultural Society in September 1990.

Since then, they have repeatedly applied to register with the

proper authorities in accordance with the procedures laid down

by the authorities. They were told that that was the time for

re-registering the existing organizations and that new

organizations would have to wait. It was under those

circumstances that they formed the preparatory group for the

founding of the society at the suggestion of the propaganda

department of the Ih Ju League communist party committee.

Document No.13 of the Inner Mongolia Communist Party committee

accuses them of “trying in vain to gain legal status.” But it

is stipulated in explicit terms in the Constitution of the

People’s Republic of China that people enjoy the freedom of

association. We would like to know if the Inner Mongolia

Communist Party means to accuse this particular stipulation in

the Chinese Constitution drawn up under the auspices of the

Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party.

Secondly, six scholarly lectures were organized and

Huchuntegus and Wang Manglai wrote four or five articles after

the preparatory group was formed. All these activities had the

approval of the local authorities concerned. The articles were

also sent to the concerned officials to look over. There is

nothing in them that violates the law or “attacks” the Chinese

communist party or government. Yet, the authorities hold that

in his "Letter to Mr. X"13 (In Mongolian) Huchuntegus “incited

nationalist sentiments and created national splits, and

vilified” communist cadres. In the introduction to his article

“The Past, Present and Future of Mongolian Culture,” Wang

Manglai discussed three adverse influences suffered by

Mongolian culture since the Ching (Manchu) Dynasty, the latest

being the impact of the “red culture.” This was accused by the

authorities as “anti-communist party and anti-socialist

system,” and an “attempt” to overthrow the leadership of the

communist party." What this amounts to is obvious: “If you are

out to condemn somebody, you can always trump up a charge,” as

the Chinese saying goes.

Thirdly, in 1990, a book entitled On the Threshold of the

Twenty-First Century14 was published in Ulan

Bator, Outer Mongolia. In order to acquaint the members of the

proposed society with the thoughts and aspirations of fellow

Mongolians in Outer Mongolia and the problems the latter are

facing, the preparatory group of the society translated that

book into archaic Mongolian, typed and mimeographed scores of

copies at its own expense for members of the society to be

passed on to one another among themselves. This was considered

by the authorities as evidence of “hostile international

forces” trying to “infiltrate and influence Inner Mongolia.”

But at the same time, books that are far more tendentious than

the one in question in advocating “liberalism” and “peaceful

evolution” are readily available at bookstores all over China.

To cite just one example, former president Richard Nixon's

1991: Winning Without War (in Chinese translation). Original

and pirate editions from Hong Kong and Taiwan are also openly

sold in mainland China. All kinds of “reference materials for

internal use” and “printed and distributed for internal use”

as well as “materials,” “conference proceedings,” etc. put out

by various organizations and units are literally everywhere.

Many of them reflect Western point of view and advocate

“bourgeois liberalization.” Yet these are not considered by

the authorities as propagating liberalization and negating

communist party leadership. Only Mongolians who did the same

thing are languishing in prison.

In

fact, the Chinese authorities use a double standard in

handling political problems on different nationalities. The

Mongolians do not enjoy equal political rights as the Han

people. In China, the political persecution of minority

nationalities is more severe and the latter’s human rights

conditions are worse. Any word or deed that upholds ethnic

interests or show dissatisfaction with the status quo would be

labeled by the authorities as “creating national splits” or

“undermining the unification of the motherland and the unity

of nationalities.” And such charges can be trumped up at will

according to the needs of the authorities.

The

fate of the other members of the society:

Personal freedom of the other 26 members of the society has

been restricted by the authorities since the arrest of Huchun

and Manglai. They are not allowed to move around a will or

associate with other people. They were repeatedly questioned

and intimidated by the local party and government offices and

the secret police of the public security and national security

bureaus. Some of them have been summoned and questioned a

dozen times. On one occasion, Sechenbayar a member of the

society and a research fellow at the Ih Ju League Genghis Khan

Institute, was questioned by the police continuously for 12

hours from 4 p.m. on June 12 to 6 a.m. the following morning.

During these questioning sessions, the police illegally used

intimidation, insults and corporal punishment, trying to force

or trap them into a confession. They were ordered to sit still

with their hands on their knees and motionless for long

stretches. The police also threatened them not to talk about

their experience with the police. The authorities indicated

that some of the 26 members will also be arrested, most

probably eight of the more active ones.

The

party organizations and administrative leadership of the

places of work of these members of the society have received

orders to put pressure on them, to perform “ideological work”

and persuade them to voluntarily “confess” their “crimes” to

the authorities. As members are constantly subjected to

persecution, their families are also under tremendous mental

pressure. Some are suffering from serious insomnia. Others are

extremely nervous, even exhibiting certain symptoms of nervous

breakdown.

This

is not all. The Ih Ju League authorities, under orders of the

Inner Mongolia communist party committee, are launching a

mandatory study campaign throughout all banners of the league

and the Municipality of Dongsheng. Party and government

cadres, intellectuals, workers and students are called on to

identify themselves with Document No.13 issued by the Inner

Mongolia communist party committee, repudiate and expose the

crimes of national splittism and bourgeois liberalization. It

is not clear as of now how long that campaign will last.

*

During the pro-democracy movement of 1989 in Beijing, there

were also large-scale demonstrations and students boycotted

classes in Hohhot, Baotou and other Inner Mongolian cities.

After “June 4,” the authorities also cracked down on the

participants of the pro-democracy movement. Wang Qun,

secretary of the Inner Mongolia communist party committee, was

one of the local leaders who advocated suppression most

vehemently and the first “prince” to come out in support of

the June 4 massacre. He is also remembered as the first of the

party secretaries of the various provinces and autonomous

regions to cable his respect to Deng Xiaoping and the other

“proletarian revolutionaries of the older generation,” who

ordered the Beijing massacre. But Wang Qun’s barefaced

flattery and boot-licking did not win him the appreciation of

the “veteran revolutionaries.” Instead, he became a

laughingstock of the common people. In the past two years, the

20 million Mongolian and Han people in Inner Mongolia became

familiar with the way Wang Qun appears on television, with his

arms akimbo or waving in the air and shouting at the top of

his voice. Especially when he abuses “bourgeois

liberalization” and the “national splittists.” he glares and

his eyeballs bulge. Those are indeed his outstanding

characteristic features.

Around June 4 of last year and this year, posters were put up

and handbills distributed in Hohhot and other Inner Mongolian

cities, commemorating June 4, demanding democracy and human

rights and opposing national oppression and discrimination.

The authorities were frightened. They sent many plainclothes

secret police and agents to university campuses. Many teachers

and students were watched and followed. “Reactionary slogans”

were discovered on the blackboard in a classroom of the

Mongolian language department of the University of Inner

Mongolia around June 4 of 1991. They read “Long live

democracy” and “Long live the Kuomingtang.” More than forty

students who used that classroom were questioned by police one

by one. Several days later, the police arrested Zhang Haiquan

(an ethnic Mongolian), a journalism sophomore. It is not known

where he is being held.

*

According to reliable information, after the arrest of

Bayantogtokh, leader of the Bayannur League of National

Modernization Society, which was branded an illegal

organization by the authorities, he was secretly tried and

sent to Hohhot. He is also being held in the prison

administered by Section 5 of the Public Security Bureau of

Inner Mongolia- Seven members of that society were escorted by

the police to the Municipality of Linhe and questioned there.

Their whereabouts are not known.

*

The fact that the crackdown in Inner Mongolia has attracted

the attention of the international community has greatly

encouraged the people of Inner Mongolia. On May 12 and 14,

many people said they heard the Chinese language program of

the BBC, which reported on events in Inner Mongolia. VOA also

reported those events on June 21. Others reported that news

stories of those events appeared in the Hong Kong Times

(XianggangShibao),Ming Bao and a newspaper in Taiwan.

They are looking forward to learning more from those sources.

*

The disclosure of what happened in Inner Mongolia by foreign

media angered Beijing and Inner Mongolia authorities. They

considered it a serious political matter. According to the

Hong Kong Times, the Chinese authorities are convinced

that a human rights organization is active in Inner Mongolia.

They have ordered the public security and national security

departments to crack the human rights organization case as

soon as possible.

In

addition, the authorities are tightly blocking the passage of

the information about recent events in Inner Mongolia. The

Inner Mongolia communist party committee has ordered the

recall of the top secret Document Number 13 of 1991 issued by

its office to the various units.

Recently, a BBC correspondent called the Ih Ju League

Department of Education about the arrest of Huchuntegus and

others, the person who answered the phone found out the caller

was a correspondent and he reported to the leadership. It was

announced at a meeting of government employees [MS not clear

here] that no information about Huchuntegus and Wang Manglai

could be disclosed to anyone.

*

After the events in IhJu and Bayannur Leagues, Wang Qun became

convinced that there are also “illegal organizations” and

“national splittist elements" in the other six leagues and

four municipalities directly under the autonomous region.

Therefore, as he sent large numbers of public security and

national security agents to IhJu and Bayannur Leagues, he also

deployed secret police in Hohhot, the capital city of Inner

Mongolia, and other leagues and municipalities to make sure

that more “illegal organizations” will be unearthed.

According to reliable information, a task force of some thirty

people was set up headed by Li Maolin, Director of the Public

Security Bureau of Inner Mongolia, to unearth the “illegal

organizations.” It is empowered to muster the entire police

force of Inner Mongolia. And it is made up of police officers

of the ranks of section and department chiefs or above, who

are considered absolutely trustworthy by the authorities. They

are acting in utmost secrecy.

The

authorities in Beijing have been following development in

Inner Mongolia over the past months with great interest. Jiang

Zemin. Li Peng and Qiao Shi have all given instructions on the

work in Inner Mongolia. In order to step up the suppression,

the Beijing authorities have transferred large numbers of

experienced public security and national security agents from

Beijing, Hebei and Shanxi to Inner Mongolia. The Ministry of

Public Security has also sent trouble-shooters to assume

command there.

The

authorities are enlarging the scope of their investigations

and persecution. More and more people are being secretly

questioned, watched and followed. An increasing number of

students, teachers, care and workers are becoming suspects.

Some high-ranking ethnic Mongolian officials have also become

targets of investigations. Panic and unease are spreading.

According to some sources, the authorities have expanded their

investigations to ethnic Mongolian college students studying

in universities in the Xianjiang Uigher Autonomous Region and

Gansu, Liaoning and Henan provinces. These students are or

will soon be facing persecution.

*

The Second Convention of the Inner Mongolian Association of

Philosophy and the Social Sciences was held May 10-12. Wang

Qun and Bu He, president of the Inner Mongolian Autonomous

Region, attended the convention. Wang Qun twice interrupted

presentations by professors and in a harsh tone demanded if

they knew an illegal organization had been unearthed in Ih Ju

League. He then lectured them, claiming that academic issues

were in fact political issues, and that the domestic and

international class enemies were using academic research to

split the nation and undermine the unity of the motherland. He

repeatedly stressed that one of the four ways domestic and

international enemies carried out their “peaceful evolution”

and subversive activities was to recruit agents from among the

high-ranking party and government leaders. That comment gave

high-ranking ethnic Mongolian officials the jitters. It also

aroused resentment and disgust among ethnic Mongolian

intellectuals and cadres. Even Han intellectuals were angered

by those comments.

*

The policy of the Beijing authorities toward Inner Mongolia

became harsher over the past few months. In addition to

political and economic measures that were inimical to ethnic

Mongolians, the authorities have also taken action in

education.

At

the end of 1990, Guo Fuchang. director of the Department of

Education for Minorities of the State Education Commission,

jointly with Bai Ying and Jin Daping, respectively head and

deputy-head of the Inner Mongolian Department of Education,

proposed at the Conference on Education Work in Inner Mongolia

that, beginning with first graders, the study of the Han

(Chinese) language would be mandatory for all pupils of the

ethnic Mongolian primary and middle schools, that hereafter,

minority education in Inner Mongolia would be conducted as

much as possible in the Chinese language, and that fewer

special Fields of study and fewer students would be taught in

the Mongolian language at the universities.

The

“All Inner Mongolian Conference on the Teaching of Minority

Languages in Primary and Middle Schools” was convened by the

Inner Mongolian Department of Education in Kulun Banner of

jirem League on June 10-15. At that conference, the above

instructions were communicated to conference participants.

Those instructions were strongly opposed by some sixty

educators who attended the conference. These participants held

that the instructions were tantamount to compulsory

sinicization of the Mongolian nation and total destruction of

Mongolian culture and education.

In

fact, the new policy of the State Education Commission and the

Inner Mongolian Department of Education met with strong

opposition from the ethnic Mongolians at its inception. Last

spring, ethnic Mongolian teachers of Jerim League collectively

wrote a letter to Jiang Zemin to protest the policy. They

warned that the implementation of that policy would trigger

large-scale protests and demonstrations in Inner Mongolia.

This matter has now become the focus of attention of the

ethnic Mongolian cultural and educational circles throughout

Inner Mongolia.

(end

of report)

Appendix

II

On

Further Stabilizing the Minority Areas in the Frontier

Regions:

the

Situation and our Views

byJiang

Zemin

March 10.

1990

Comrades:

Today, we invite comrades from minority areas in the frontier

regions as well as those from the greater military areas of

Shenyang. Beijing, Lanzhou and Chengdu, who are attending the

current plenary session of the central committee, to a forum.

At the same time, we have also invited those comrades from the

various departments of the central committee and the relevant

ministries of the state council attending the plenary session

to take part in a discussion of the problem of further

stabilizing the situation in minority areas in the frontier

regions. Premier Li Peng, comrades Qiao Shi and Song Ping and

comrades Ding Guangen and Yang Baibing are all attending

today's session. This shows that the central committee of the

party, the state council and the military commission of the

central committee are all following with great interest and

attach great importance to the work in minority areas in the

frontier regions.

At

this plenary session of the central committee, we are going to

make an important decision to strengthen the link between the

party and the people, to carry forward the fine tradition of

the mass line. For work in minority areas in the frontier

regions to be successful and to maintain stability of the

situation on the frontiers, we must also unswervingly unite

with and rely on people of every ethnic group, on

military-civilian unity, and together build a solid and

civilized frontier defense, making it truly impregnable.

A

short while ago, comrades Song Hanliang, Bu He and Hu Jintao

talked about the situation in Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia and

Tibet respectively, and offered some good experiences and

opinions. In what follows, I will speak on the situation and

our opinion on further stabilizing the situation in minority

areas in the frontier regions.

I.

Looking at the situation as a whole, our

frontier regions are stable.

In

the present international and domestic climate, our minority

areas in the frontier regions are able to maintain stability

primarily because, in my opinion, of the following factors:

(1) Over the long course of history, our various ethnic

groups have formed a unified multi-national state. In the past

century and more, in particular, people of all ethnic groups

suffered from invasion, bullying, oppression and exploitation

at the hand of the powers. In their struggles against foreign

domination, the force that holds the various ethnic groups

together, the centripetal force, has become greatly

strengthened, and the “Chinese nation” has become the common

name shared by all who are in the same boat and who go through

thick and thin together.

(2) Proletarian revolutionaries of the older generation

have drawn up a whole set of policies toward the minorities

that integrates the Marxist-Leninist nationalities theory with

the reality of China’s nationalities and fits China's actual

conditions. These policies have manifested specific Chinese

features in the following three ways: first, the principle of

equality for all ethnic groups irrespective of their size. At

a meeting of the central committee in 1953, Chairman Mao, in

summing up, made it clear that “it is all right to make

scientific analysis. But politically we should avoid

distinguishing among a nationality, an ethnic group, or a

tribe.” In accordance with this instruction, the party and

government determined that all stable communities of people

living in China are to be called “nationalities” irrespective

of the size of their population or territory, the stage of

their social development, or whether the main body

of

their population lives within China's borders, provided they

share distinctive features in economic life, spoken and

written language, costume, customs and habits and national

consciousness. At that time. the state council issued a notice

lo abolish or change the place names and names of

nationalities left over from the old China that were insulting

to the minorities. Secondly, regional autonomy of minority

nationalities has become the basic institution for solving

China's nationalities problem, and the slogans of “national

self-determination” and “federalism” have been discarded. As

early as October 23, 1945, the central committee of our party

pointed out: “Our basic policy towards Inner Mongolia at the

present time is to institute regional autonomy.” On February

18, 1946, the central committee pointed out further that “we

demand equality and autonomy for the nationalities in

accordance with the program for peaceful national

construction. But we must not put forward the slogan of

independence or self-determination.” On May 1, 1947, we

established the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region. Thirdly, we

have upheld the policy of unity, progress, close cooperation

and mutual promotion. In 1952, the central committee issued

the “Opinions in principle on the 5-year construction plan for

minority areas,” which explicitly formulated the basic task of

nationalities work as instituting regional autonomy for the

minority nationalities, developing their economy and culture,

and strengthening and consolidating national unity. In the

past forty years, the cause of China's national unity and

progress has achieved brilliant successes. Especially since

the third plenary session of the eleventh central committee,

and with the shift in the focus of our work, the minority

areas and the minorities have made remarkable progress, and

the basis for national unity has been expanded and

strengthened.

(3) After we suppressed the disturbances and rebellion that

broke out last year in Beijing and some other cities, we

strengthened our work in minority areas in the frontier

regions. Last September, the state council issued its document

No. 62 and called a work conference on helping the poor in the

minority areas. I made a speech at that conference. In

October, the central committee of the party made a special

study of the Tibetan question, after which the “Summary of

Minutes of the Politburo Party Committee’s Discussions at the

Conference on Work in Tibet” was issued. The party committee

of the Tibetan Autonomous Region conscientiously communicated

that document and carried out the instructions. In January and

February of this year, after the central committee of the

party and the state council issued a circular on changes in

the situation in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, the

various areas promptly studied the document and carried out

the instructions. Xinjiang, Tibet and Inner Mongolia convened

standing committee meetings, made a special study of the work

to stabilize the situation and took measures. In mid-February,

the party central committee and state council heard a report

of the meeting of the commissioners of the nationalities

commissions of the country. I and Comrade Li Peng both spoke

at the meeting. Our speeches and instructions are being

transmitted and carried out. All this played an important role

in maintaining stability in minority areas in the frontier

regions. February 26 was the New Year of the iron horse

according to the Tibetan calendar. A festive air of joy and

celebrations prevailed in areas where ethnic Tibetans live in

compact communities, including Lhasa. The situation in Lhasa

was also stable on the 5th and 10th of March, [anniversaries

of uprisings-tr.]

II. Even as we fully affirm our achievements, we must

attach great importance to eliminating all sorts of elements

of instability in the frontier regions.

(1) Splittists both within and outside of the country and

other reactionary forces have never ceased their disruptive

activities. The Dalai clique of Tibet, the Isa clique15

of Xinjiang and “Mongolia” of Inner Mongolia established

their joint setup in Switzerland two years ago. It is

publishing its organ periodical in New Delhi. Some splittists

have joined force with those reactionary elements who are

trying to bring about bourgeois liberalization. Some people

are looking in vain for “Timisoara” in China’s minority areas.

Not long ago, Dalai even went so far as to openly ask us to

take the road of the Eastern European countries, and

threatened to change his conciliatory stand. Splittists within

and outside of Tibet have stepped up their disruptive

activities. In Luolong County of Changdu area, three cases of

bombing, murder and reactionary slogan took place in a single

day. The “Democratic League” and other opposition groups in

the Mongolian People’s Republic [MPR] claim to have the

support of their “Mongolian brothers and sisters” within

China’s borders. There are some in the MPR who are vainly

trying to establish a so-called Greater Mongolian state that

would include the Buryat (ethnic Mongolian) Autonomous

Republic of the Soviet Union and also our Inner Mongolia. The

slogans used by the reactionary elements within and outside

both Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang are extremely similar -- for

example, “No nuclear testing,” “Against the plunder of our

resources,” and “Drive away the outsiders.”

(2) Compared with other areas of the hinterland, the

frontier regions lag far behind in economic and cultural

development. To this day, some of the minority people still do

not have enough to eat and wear. Certain areas and departments

are negligent of the nationalities question in their work.

They apply the same formula to quite different cases.

Development of resources in minority areas by the state gives

a great impetus to the growth of those areas. But insufficient

attention has been paid to local development and the interests

of the minority people. To tackle these problems step by step,

the state council has taken and is still taking the necessary

measures. Work to help the poor has been very effective. But

still greater efforts are needed to have the policies and

measures properly implemented. Bridging the gap is a long-term

tasks.

(3) As a result of the lack of breadth and depth of the

work of propaganda and education in the Marxist view and

theory of nationalities and the party's policy towards the

nationalities, and especially the inadequacy of the education

of youngsters, part of the writers and artists and cadres,

incidents that hurt the feelings of the minority people on

such sensitive issues as customs and habits and religious

belief still occur from time to time. There are very close

links between those minority people who live in compact

communities in the frontier regions and those who are

scattered in the hinterland. An incident in one place rapidly

impacts on another. The book on “Sexual Habits” touched off

considerable commotion.16 Tens of thousands took to

the streets in Urumchi and Lanzhou. They rushed the leading

organs, vandalized and burned automobiles.

We

take the above-mentioned problems and other elements of

instability very seriously and shall tackle them in real

earnest. We would rather regard the problems as more serious

than they really are so as to heighten our vigilance and

provide against possible trouble; we must never lower our

guard.

III. In the days to come, work in several fields must be

conscientiously done well.

On

the whole, provided we uphold the set of principles and

policies that has stood the test of practice, closely unite

with and firmly rely on people of the various nationalities

and work had to perform our tasks well, we shall be able to

ride out the storm, continue to maintain stability in the

minority areas in the frontier regions, and steadily improve

the situation there. Otherwise, rather big problems and

troubles may crop up in the present climate and as a result of

incitement and disruption on the pan of the hostile domestic

and foreign forces.

(1) Take a clear-cut stand in fighting divisive activities

and infiltration. Those who engage in divisive activities are

always in the minority. But we must maintain sharp vigilance

and beware of the disruption and damage they could inflict on

us, unite with and rely on the broad masses of the cadres and

people and wage a resolute struggle against them. We must take

the initiative to eliminate hidden danger and take effective

preventive measures. At the same time, we must draw up advance

plans to deal with emergencies so as to be prepared against

every contingency. We must try as much as possible to nip the

disruptive activities in the bud and never allow them to grow

and spread. We must also be on guard against those who try to

infiltrate under the cloak of religion and take preventive

measures.

(2) We must promote economic and cultural development in a

down-to-earth manner. It is especially important to achieve

solid economic growth, show solicitude for people’s

livelihood, and solve the problem of providing adequate food

and clothing for the people once for all and as quickly as

possible, help them shed their poverty and become well-to-do,

and advance towards prosperity for all. Those measures adopted

by the state council that have proven effective must be

implemented in earnest. In the days to come, our policy should

further favor the poverty-stricken areas and areas of the old

and the young. While stressing self-reliance, it is also

necessary to give them assistance and support.

(3) Continue to open up the minority areas in the frontier

regions to the outside world, develop good-neighborly and

friendly relations and border trade, as well as economic and

technological cooperation. At the same time, border trade must

be effectively managed, so that it can play a positive role

and its negative side can be overcome and it can develop in a

healthy manner.

(4) Step up propaganda and education in the

Marxist-Leninist-Maoist view of nationalities, focusing on

leading cadres at all levels, intellectuals and young people.

Sensitive issues likely to ignite mass emotions should be

promptly handled properly and with prudence. Propaganda and

public opinion shaping should be conducted successfully,

starting from the desire to strengthen national unity and

stabilize the overall situation. For example, some minority

people take exception to such formulations as “descendants of

Emperors Yan and Huang” [generally regarded as the ancestors

of the Han people-tr.]. We may consider using such phrases

domestically as the “Chinese nation,” “sons and daughters of

China,” so as to better appeal to the minorities. Again, for

example, in propagating certain historical events and figures,

one could learn from the spirit of the then premier Zhou Enlai,

when he urged dramatists to write historical plays about

“Princess Wencheng” and “Wang Zhaojun” [Chinese princess and

court lady married to minority chiefs-tr.]. We must uphold the

historical materialist stand, guide the people to look

forward, and promote the unity among the various

nationalities.

(5) We must adopt effective measures to enforce in full the

"Law of Regional Autonomy for Nationalities," and promptly

enact the necessary decrees for this purpose. The key to

enforcing the said law is to foster large numbers of cadres

and all sorts of qualified personnel, who have both ability

and political integrity. It is especially important to foster

high-ranking minority cadres, who are versed in the

Marxist-Leninist-Maoist view of nationalities.

(6) Step up the building of our frontier defense. The

frontier guards are an important force in stabilizing the

situation in the frontier regions. Effective measures must be

taken to solve the problems and difficulties the frontier

guards are facing. We must strengthen the joint defense of the

guard units, the police and civilians, and effectively wage a

struggle against infiltration and subversion, safeguard the

normal order of openness to the outside world, defend the

frontiers and the security of our country.

Comrades: The minority people in the frontier region love the

party and socialism ardently. I personally experienced this

last year, when I visited the area where the Jino people live

in compact communities in Xishuangbanna Prefecture ofYunnan

Province. We shall be able continuously to maintain stability

in the minority areas in the frontier regions and promote all

our undertakings successfully, provided we serve the people of

all nationalities wholeheartedly, rally them together closely

and rely on the cadres and people of the various nationalities

and perform our tasks well.

(This document is issued to the provincial and army levels. In

the provinces and

autonomous regions of minority areas in the frontier regions,

it may be transmitted to units at the county and regimental

levels. Copies may be printed as needed, but must be strictly

controlled.)

Appendix III

SECRET

Document of the Office of the Peopled Government

of

the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region

Inner/Government/Office/Issue (1991) No. 45

March 29. 1991

Circular on Matters Needing Attention of Citizens

in

Their Contacts with Foreign Nationals in the Open

Cities and Areas of Our Region

To

the administrative offices of the various leagues, the

municipal people’s governments, the banner, county (municipal)

people’s governments concerned, the various commissions,

offices, departments and bureaus of the autonomous region, and

the various major enterprises and institutions:

In

the wake of the extensive and deepgoing development of reform

and openness of our region, citizens in the cities and areas

open to foreign visitors have come into increasing contact

with foreign nationals. In order to ensure that the party’s

foreign policy is faithfully carried out, the discipline in

conducting foreign affairs is strictly observed, and the

people are guided to adhere to the principles governing

foreign affairs activities and contacts with foreign

nationals, we list the following points of attention in

accordance with the principle enunciated in recent years of

tightening the control of dealings with foreign nationals. All

units are expected to propagate them and educate the cadres

and masses in them, and overcome existing unhealthy

tendencies, so as to improve our foreign affairs work.

1. In dealing with foreign nationals, it is necessary to

work for friendship, to promote friendship with people of all

countries of the world; to demonstrate ardent love for the

motherland and national integrity; to uphold state and

national dignity; pay attention to our national style and

one's personality; be particular about one’s demeanor and

bearing; be civil and polite, modest and prudent; behave with

self-respect, neither supercilious nor obsequious.

2. Treat all foreign nationals equally without

discrimination, irrespective of the color of their skin, the

size of their country, their rank, their customs and habits,

or their religious belief. Be warm and friendly and polite,

avoid favoring one and be prejudiced against another, or

detesting the poor and favoring the rich. In dealing with

foreign nationals, one must have a sense of propriety and

consider the possible political effect. Be prudent in

expressing one’s views on sensitive international domestic

issues, so as to avoid unnecessary disputes or incidents in

foreign affairs.

3. In dealing with foreign nationals, one must uphold the

four basic principles, oppose bourgeois liberalization and

watch with vigilance the infiltration by hostile foreign

forces. It is necessary consciously to implement our country’s

foreign policy, uphold the “One China” principle, and oppose

any attempt to create “two Chinas” or “One China One Taiwan,”

and words and deeds that undermine national unity. One must

safeguard the unity of the motherland, defend state

sovereignty and territorial integrity.

4. One must strictly keep party and state secrets, be on

the alert for foreign nationals who try to pry and spy out our

restricted information. Once it is discovered that foreign

nationals who engage in collecting intelligence, spreading

rumors, stirring up trouble or other illegal activities, it

must be promptly reported to one's organization as well as the

security organ of the state. Do not hint to foreign nationals

that oneself or one’s children would like to go abroad.

Generally speaking, foreign nationals should not be invited to

one’s house. No one is allowed to get in touch or contact

foreign embassies or consulates in China without

authorization. Do not give one’s name and address and those of

one’s home and unit to foreign nationals who are total

strangers and whose background is unknown.

5. Exchanging currencies with foreign nationals, asking

them for money or gifts, or to buy on one’s behalf commodities

that are in short supply, forcing them to buy things from

oneself, or asking them to pass on appeals or petitions are

prohibited. No one is allowed to take advantage of his (her)

dealings with foreign nationals for personal gain, or engage

in activities that are harmful to the interests of our country

and our people.

6. Should foreign nationals request to meet with their

Chinese friends or relatives, schoolmates or colleagues, visit

their homes, have dinner or stay overnight, this must be

approved by the leadership of the unit where the person(s)

involved work, and reported to the foreign affairs department.

In the case of staying overnight, registration with the public

security organ is mandatory according to the regulations.

7. As for those foreign nationals who go straight to our

grassroots units or residencies, their intention must be found

out. If they want to pay a visit or collect news, they should

be asked to get in touch with the local foreign affairs

department through the unit that received them. Those who

ignore our dissuasion and try to crash the gate must be

promptly reported to the relevant department for proper

handling.

8. In case foreign nationals ask by mail for certain

information about our country, or try to locate their old

acquaintances of pre-liberation days, the recipients of those

letters should promptly inform the relevant departments and

decide whether to supply the requested information. If the

background of the letter sender is not known, or the person he

is trying to locate is unfit for foreign dealings, the

communications should be ignored.

9. Do not fill out the questionnaires or forms sent by

foreign nationals or institutions. Instead, these should be

reported to the leadership of the unit where one works, or to

the foreign affairs department in charge for study, so that

the matter could be settled as it sees fit.

One

may submit manuscript(s) if solicited by foreign countries.

But no restricted information should be disclosed. One must

not respond to those solicitations if the background of the

sponsor is unknown, or the contents solicited run counter to

China’s foreign policy or to China’s national conditions or

the prevailing moral standards.

10. Books, periodicals and materials sent by foreign

professionals to their Chinese colleagues may be accepted if

these are truly valuable reference materials. Chinese

professionals may also send them our books, periodicals and

materials in return. But these materials must be openly

published ones. Any unpublished material must be reported to

the leadership of the unit concerned, or to the department in

charge for approval.

11. Individuals who receive invitations or tickets directly

mailed to them by foreign embassies in China should ask for

instructions from the leadership of their units or from the

foreign affairs department. No one is allowed to attend or

transfer his (her) invitation or ticket to others without

authorization. In case foreign nationals invite Chinese

personnel to view something with all sons of tickets, they

should be politely turned down.

12. Every citizen enjoys the freedom to communicate with

foreign nationals by letters. But the letters must not touch

on China’s secrets. One must not send souvenirs to leaders of

foreign governments without authorization, nor ask for their

inscriptions or autographs, so as to avoid unnecessary

troubles. Recipients may write to thank foreign nationals for

letters of thanks or greetings and group pictures received.

13. Foreign nationals may take pictures wherever they are

allowed to go. Those exceptional individuals who, with

malicious designs, try to get some insulting shots should be

criticized and the incident reported to the departments

concerned. Eye-catching notices in both Chinese and foreign

languages should be put up where foreign nationals are not

allowed to take pictures.

It

is up to the person(s) concerned to decide whether to agree to

a foreign national’s request, as a friendly gesture, to have a

picture taken together with him (her). Other people should not

try to interfere.

14. Travel routes in all open areas and wherever foreign

travellers are allowed to visit must be kept open. No one is

allowed to block these routes.

15. Citizens living in areas where border posts are located

must observe the relevant provisions in dealing with foreign

nationals.

Concrete problems arising from the implementation of this

circular may be reported to the office of foreign affairs of

the autonomous region.

Copies for the various departments of the communist party

committee of the autonomous region, office of the standing

committee of the People*s Congress, office of the Political

Consultative Conference, the headquarters of the Inner

Mongolian military region, the higher peopled court, the

procuratorate, the various mass organizations and news

organizations.

Office of the People's Government of the Inner Mongolian

Autonomous Region.

Printed and issued on April 3, 1991.

Number of copies printed: 1,000.

Appendix IV

Document of the Foreign Affairs Office

of

the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region

Inner/Foreign/Issue (1991) No. 26

April 17. 1991

Urgent Circular on the Management and Reception

of

Uninvited Groups or Groups to be Invited but Already

Arriving

from [Outer] Mongolia

TO:

The administrative offices of the various leagues, the

municipal people’s governments, the various commissions,

offices, departments and bureaus of the autonomous region, the

Hohhot Railway Bureau, the Civil Aviation Administration, the

various major factories and mines and colleges and

universities:

With

the normalization and steady development of relations between

the governments and parties of China and Mongolia [the Peopled

Republic of Mongolia], exchanges and cooperation between our

region and Mongolia are increasing, interregional intercourse

is also steadily rising. A situation has emerged in which

exchanges involve extensive areas: they take place at many

different levels and through many different channels. In 1990,

892 government functionaries (including 215 guest workers)

were sent to Mongolia from our region, constituting the second

largest group sent abroad from China that year. One hundred

and eleven Mongolian government functionaries were invited to

visit our region, representing the largest group of invited

foreign visitors to China. These exchanges helped improve

mutual understanding and traditional friendship between the

Chinese and Mongolian peoples, and promote the growth of

good-neighborly and friendly relations.

In

the course of these exchanges, however, the Mongolians have

become overly impatient, overly enthusiastic and overly

unruly. A major manifestation of this is that an increasing

number of uninvited groups are coming and groups to be invited

are already arriving on their own. As far as we know, two

groups with a total of 15 members were to be invited in 1989,

but they came without waiting for the official invitation, and

all their members were functionaries at the provincial and

ministerial levels. In 1990, 15 groups, with a total of 56

members, came either uninvited or before planned invitations

materialized. In 1991, there were already nine groups with 48

members so far. The sudden arrival of these groups caused

certain difficulties and inconveniences in our reception work

and foreign affairs management. In addition, the Mongolians

often mix economic and trade exchanges with cultural ones and

are keen on exchanging personal visits. The contents of

certain agreements are rather confused, and this is not

conducive to meaningful cooperation. We hold that the problem

is primarily caused by the Mongolian side. The Autonomous

Region plans to make representations to the Mongolians side

through diplomatic channels and request that they correct the

situation. At the same time, we too need to improve our

education and strengthen our management. Otherwise, control

will become still more difficult once railway service between

Hohhot and Ulan Bator begins and the number of passengers

increases. We have therefore enacted the following provisions

for managing the visiting groups. The various areas and units

are expected to act accordingly.

1. As a matter of principle, the various areas and

departments should not receive uninvited groups or

individuals. In case the latter contact our relevant areas or

counterpart departments directly or through their consulate

general in Hohhut, the areas or departments concerned must not

make commitments on their own. If they consider the contact

desirable, they should send a written report to the foreign

affairs office of the autonomous region. With the approval of

the foreign affairs office, the visitors may be received in a

low-key manner. Both the duration of the visit and the

activities of the visitors are to be curtailed. And in

principle, no visits are to be arranged, no banquets, and our

side should not be responsible for the visitors’ room and

board and other expenses.

2. The public security and national security department

should take measures to keep close track of the uninvited

groups or individuals. The hotels, hostels, guest houses,

travel agencies and other service departments should work

closely together and at the same time ensure the safety of the

foreign visitors.

3. Once the areas or departments receive word that those

groups or individuals to be invited are coming ahead of

schedule on their own, they should be effectively persuaded

not to depart. They should be told: “We have not yet completed

the preparations for your reception. Please wait for our

formal invitation before departure.”

4. In case the group to be invited has already arrived,

the formalities of invitation should immediately be made up

according to procedures. A description of the visiting group,

the plan for its reception and the itinerary of its visit