|

|

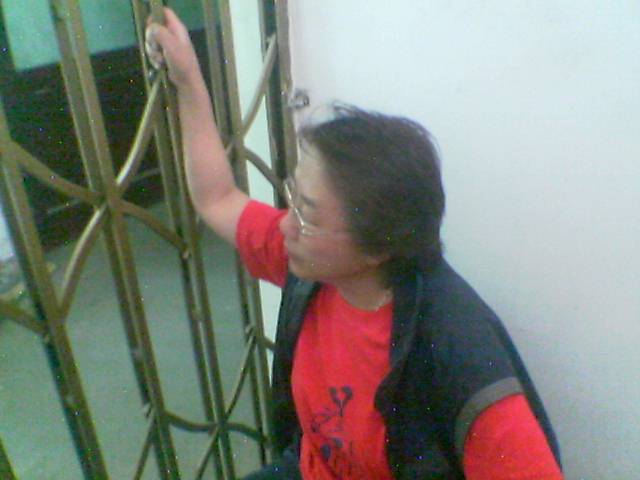

| Xinna,

detained by the Chinese authorities for

expressing her dissent at the court during

the trial of a Mongolian couple, Mr.

Naguunbilig who was sentenced to 10 years in

jail, and Ms. Daguulaa who was sentenced to

5 years in jail for "engaging in evil cult".

(SMHRIC photo) |

|

Xinna speaks with the aggrieved yet defiant air of

someone who has told her story a hundred times without

results. Sitting at a table on a Hohhot footpath sipping

Mongolian milk tea, she at first tries to ignore the

secret police who watch her meeting with a visitor. Then

she takes a more cynical approach and waves at them,

smiling.

"I

have nothing to hide. Let them watch," said Ms Xinna,

emphatic that what the government appears to be

increasingly afraid of is unlikely to happen.

While there are simmering ethnic tensions between Han

Chinese and the native Mongol population over the

latter's loss of culture and influence, Mongols are

nearly unanimous in saying they have little desire to

see a Tibet-style uprising or any active protest. The

Olympic torch will be in Inner

Mongolia between July 11 and 13.

"People have suggested to me that something could be

planned [a protest during the Olympic torch relay] but I

have refrained so far. Not many people are willing to

take those risks," Ms Xinna said. "Although sport has

nothing to do with politics, the Olympics do have

something to do with human rights. China promised better

human rights when they got the Olympics, but they have

not done that."

Ms

Xinna's husband, Hada, a Mongol intellectual and

teacher, has been in jail since 1995. He is serving a

15-year sentence for founding the Southern Mongolian

Democratic Alliance to defend Mongol rights. Human

Rights in China and Amnesty International say Hada has

been tortured in prison.

This has made Ms Xinna, who, like most Mongols, uses

only one name, a minor local celebrity, and her small

book and music shop near the Inner

Mongolia University has become a warehouse of

Mongol culture and a well-known reference point among

intellectuals. She said that although she has never done

more than peddle Mongol books and traditional music,

police surveillance of her increased dramatically after

the ethnic riots broke out in Tibet.

"In the last few weeks I've been under 24-hour

surveillance. If I go out at one o'clock in the morning

to walk my dog, there's someone sitting outside my

building," Ms Xinna said, adding that she knew of people

in the Mongol community who had been arrested in recent

weeks.

After seeing the violent backlash in Tibetan-populated

regions, it appears the government became worried that

other ethnic minorities such as the Mongols or

Xinjiang's Uygur population would also use the Olympics

to get their cause on the global stage.

"I

am understanding of what happened in Tibet because

Inner Mongolia has some

similarities," Ms Xinna said. "It [the Tibet uprising]

has been good and bad for us. After this, everyone is

talking about these problems. Some of us are proud that

the Tibetans stood up like that. They're tough."

But similar protests are unlikely in

Inner Mongolia because it lacks the critical mass

of monks that led the way in Tibet. Not only is Buddhism

central to Tibetan culture, but the monks, who have

taken the brunt of the forced cultural changes, live

together, creating a core group of protesters.

Also, there are far fewer Mongols in

Inner Mongolia than there are Tibetans in Tibet.

Mongols make up about 17 per cent of the Inner Mongolian

population compared with 79 per cent Han Chinese, while

Tibetans made up 95.3 per cent of of Tibet's officially

registered population last year.

That does not mean Mongols are content with their lot.

The government has been rapidly populating

Inner Mongolia's grasslands

with Han Chinese moved from other provinces, and the

Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Centre, a

US-based group, says the ratio of Mongols to Han Chinese

has shifted from five to one in 1949 to one to six

today.

Also central to their complaints is the government

policy of moving nomadic sheep herders - who also

include some Han - off the grasslands and into villages

and cities. Han immigrants introduced a more agrarian

society which helped to speed up the degradation of the

land, resulting in erosion problems, although the

government blames the loss of grasslands on overgrazing

by nomadic sheep herders.

Inner Mongolia sits on the

historic border between agrarian and nomadic cultures,

and this can be seen clearly when driving north from

Hohhot across the Yin Mountains, which form the southern

border of the eastern Gobi Desert. While tilled fields

were once rare on the north side of the range, the

landscape is now a patchwork of corn, oat and potato

fields.

Water is so scarce that farmers dig small holes in their

fields to catch what little rain does fall. Chronic

erosion has left hillsides slumping into ravines and

steep canyons snaking across the landscape, scars left

by summer rains.

The government has in recent years begun forcing

herdsmen to give up their nomadic lifestyle and take up

farming or work in towns and villages, in what it says

is an attempt to save the landscape.

"It is a change of identity. They are no longer

herdsmen, they are urban residents who can be affected

by modern culture and better education," said Ren Yaping,

executive deputy governor of Inner

Mongolia. "The government provides TV programmes

in the Mongolian language, books, magazines, all in

Mongolian."

The gleaming new glass and steel Inner

Mongolia Museum on the eastern edge of Hohhot

would support the government's argument that it is

providing tools to keep the culture alive, and the

museum is popular with residents.

Presented last year as a gift to celebrate the 60th

anniversary of the Inner Mongolia

Autonomous Region's formation, hall after hall of

exhibits celebrate the Mongol culture and life on the

grasslands. There is no mention, however, of how

Inner Mongolia is now a

predominantly Han Chinese region.

Any Inner Mongolian meeting, be it casual or official,

begins with Han Chinese proudly pointing out which of

those in the group are "real Mongolians". Many Han have

adopted more Mongol culture than they realise.

"The role of Mongols has changed a lot. In China's

5,000-year history the Han have not always been the most

powerful. Sometimes they were the minority and other

groups were in control," said Gangbatu, a Mongol middle

school teacher in Hohhot.

"Now we live here together, and the Chinese who live in

Inner Mongolia start to use

some Mongolian words without thinking of it. I have many

Chinese friends and they drink and eat with me in Mongol

fashion. They like milk tea and finger mutton. The

Chinese have their influences on us, and we have ours on

them."

However, the Mongolian human rights centre says an

increasing number of Mongolian-language schools have

been either forced to close or have been absorbed into

the Chinese-language school system.

Bao Erjin is a young Mongolian, but does not speak

Mongolian. "When I was in school I was told to speak

Chinese, that Chinese was my culture and language. My

parents speak Mongolian and I can understand some, but I

can't speak it," he said.

Although stories such as Mr Bao's are common, the

Mongolian language has fared surprisingly well, given

the challenges it faces. The government tried to correct

poorly written Mongolian signage ahead of last year's

60th anniversary. Most signs are bilingual.

About 4 million of Inner Mongolia's

24 million residents speak Mongolian, giving it slightly

more native speakers than Mongolia, the independent

neighbouring country. Inner Mongolia

uses traditional Mongolian script while Mongolia,

sometimes referred to as Outer Mongolia, uses the

Cyrillic text of Russia. Foreign study of Mongolian has

been concentrated in the Cyrillic form due to support

from the US, which wants to leverage Mongolia's

proximity to Russia.

Emyr Pugh, a Welshman who wrote the first commercial

dictionary software for Classical/ Uygur-script

Mongolian and lives in Hohhot translating a Mongolian

novel into English, said he was impressed by the

government's support of the language.

"It's infinitely preferable for Inner

Mongolia to be a part of China rather than of

Outer Mongolia because the culture would have been

overwhelmed by the Cyrillic," Mr Pugh said.

Most Mongols are relatively content, despite their

eroding influence, thanks to the economic boom they are

enjoying. Along with rapid expansion of mining for coal

and other minerals, the region has enjoyed the largesse

of national investment programmes.

"Inner

Mongolia is the only region to enjoy the benefits

of two national development programmes: the western

region development plan and the rejuvenation of

northeastern China. This has been a big help to our

economy," said Mr Ren, the deputy governor.

Investment in Inner Mongolia

totalled 1.35 trillion yuan ($1HK.51 trillion) between

2003 and last year, compared to virtually no investment

before that period, he said. About 75 per cent of that

money came from outside the region.

And the possibilities the money brings are not lost on

young people eager to join the economic boom, be it led

by Han Chinese or Mongols.

"I'm happy that we're part of China and not Mongolia,"

said Wu Riya, a young Mongol woman who moved to Hohhot

from the west of the region to study English at the

Inner Mongolian University. "They're lazy and

undeveloped. We get more development from China."