|

|

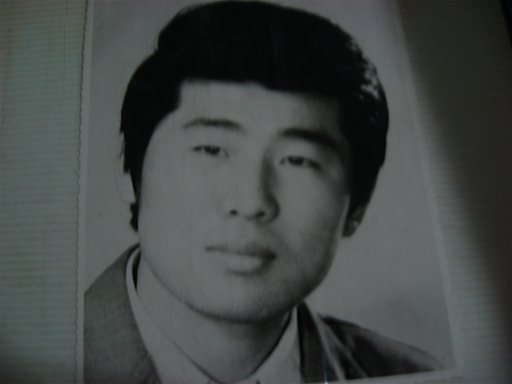

| Tumen-Ulzii

Bayunmend, Inner

Mongolian dissident

writer, when he was

younger

|

There's nothing to remind me of how far I still need to go with studies of the Mongolian language like trying to say to someone who knows no English: "the dominant language is a symptom of political authority." He is a writer in exile, and he has just asked why I wanted to learn a little, 'unimportant' language like Mongolian. After all, it's not like Spanish, which half the population of my home state speak. Hardly anyone who does not grow up speaking Mongolian endeavors to learn it, something I learned while looking for a summer language course and finding only one official one in the USA. But it has become more important to me every time I travel to a developing country and see some scantily clad blonde actress on the side of a bus to find ways to participate in regional culture in the ways I can. Now, to be clear: I love American pop culture. I think it's hilarious and totally entertaining and my favorite movies are romantic comedies. But I am, as Slug puts it, trying to find a balance, and since I am better at language than I am at herding camels, learning the Mongolian language is my way to honor regional culture--and express a little political subversiveness.

I was born where people speak the language being imposed on the globe, the language people in Mongolia and many, many other countries save up their money to be ble to take classes and study--because without knowledge of the English language, a well-paying job here is virtually ungettable. And of course, since no translation is ever perfect, a different version of reality/truth is expressed by each different language, and learning an obscure language is outfitting oneself with a new filter through which to understand reality. And that, that's always scary to People in Power.

One of the biggest honors I have had

since moving to Mongolia and

starting my work with writers was

meeting Tumen Ulzii, this Inner

Mongolian living in exile here in UB

(Inner Mongolia is in China). He is

40 years old, soft spoken, very

kind, and the Chinese police went

after him three times in 2005 until

he finally came here. The offensive

documents were books of essays he'd

written (in traditional Mongolian

script, which Inner Mongolians still

use over cyrillic) about politics,

race, and society. Writers in exile

are a living, suffering reminder of

how high the stakes can get for

those of us working in the field of

the written word. I remember

something Linda Oppen said to me of

the years her parents, Mary and

George Oppen, spent in Mexico during

the 1950s McCarthy-era emigration of

many American artists. Linda was a

young girl at the time and I said it

must have been fun living in Mexico

with a house full of animals like

they did. Linda gently reminded me

that a life in exile is not a happy

life, and that her parents were

deeply unhappy in many ways during

their time there. Ten years away

from home. And for refugees--those

whose homes are obliterated and

never there to go back to--too many

people to count live this reality,

and it's one I can't imagine, a

tragedy of the heart too deep for me

to see. While there are certain

things I learn when I study new

languages, how it feels to be forced

out of one's home is not one of

them.

January 2008

The day is clearer and much colder

in Tumen-Ulzii and I walk the five

minutes from my apartment to the

Mongolian branch of the United

Nations. Uniformed men in their

early twenties guard the compound.

We move beyond, to the UNHCR office,

where I ask one large Mongolian man,

Mr. Och, what the holdup is on

Tumen’s refugee status.

Refugee situations are never easy,

and this is no exception. Mongolia

has no UNHCR branch, only a liaison

office, so the decision to grant

refugee status has to come from the

nearest branch, which happens to be

in…Beijing. Mongolia also has no

provisions in its law for asylum

seekers, so as long as Tumen remains

one he was at risk of deportation

and then punishment at the hands of

the government whose officials

stormed his house, strip-searched

his wife, and arrested his friend

Soyolt, another Inner Mongolian

dissident, on January 7th, 2008 upon

touchdown in Beijing on a business

trip. (Soyolt was in the

incommunicative world of arbitrary

detention without charge or trial

somewhere in China while his wife

and three children remained in

Ulaanbaatar for six months.) The

imminent Olympic Games in Beijing

seem to be both a blessing and a

curse for Chinese dissidents;

attempts by the Chinese government

to silence them in the buildup to

the Games have resulted in multiple

situations like that of Tumen and

Soyolt, but the unprecedented amount

of attention the international

community is currently paying to

China’s human rights record can also

serve as a form of inoculation for

the lucky ones who get noticed.

Mr. Och at UNHCR tells me to secure

a letter of support for Tumen from

Freedom to Write at PEN New York,

and then that a decision should come

in the next week, which is something

he will tell me for three months.

Afterwards Tumen and get beer. Tumen

loves that I like beer. It's

midafternoon, but around here people

drink beer at lunch, at least the

demographic I work with (read:

middle aged male writers).

Bayarlalaa, minii okhin, he

says. Thank you, my daughter.

Sain okhin, he says. Good

girl.

Tumen is extremely quick, but there

are some things he says that boggle

me. He can understand lesbianism,

but not male homosexuality, and he

wants to know why it exists—and how

the sex happens. He thinks Hitler’s

fine, since he wasn’t as bad as

Stalin. He likes President Bush,

purely because Bush is the President

of the U.S.A.

He does have a few good friends

here. Uchida is a gentle Japanese

man and a great friend of Tumen’s. I

meet with both men several times at

the pub around the corner from where

I live. I write up a bio of Tumen to

forward to PEN’s Freedom to Write

program, and the men check over it,

Uchida translating, while I dig into

fried meat and rice. Though they are

both in their forties they look and

sound like school buddies hunched

over a cheat sheet, casual and

affectionate. Afterwards, I tell

them I need to go and clean my

floor. They say they would like me

to stay and drink beer with them

instead. “Tomorrow,” Uchida says,

and at the same time one man mops

with an invisible mop and the other

sweeps with an invisible broom.

In the pub Tumen scribbles in traditional Mongolian script. My Mongolian teacher, Tuya, is the only younger Mongolian I’ve met to know traditional Mongolian script, which Inner Mongolians still use exclusively. Tumen, fluent in Mongolian, Japanese, and Chinese, is confounded by Cyrillic type. Though it was only instituted in 1944, It has taken deep hold here in (Outer) Mongolia. The pages of Tumen’s notebook are covered in the rows of lacy black script whose verticalness, Mongolians say, makes you nod yes to the world as you read instead of shaking no.

Inner Mongolians see themselves as part of a larger Mongolia and maintain that Inner Mongolians helped Outer Mongolia to achieve independence. This view is not shared by the Outer Mongolian public, and anyone from any part of China is at physical risk here--as the “f*cking Chinese go home” graffiti outside my apartment and the recently acquired black eye of my young Chinese friend Li, who is here to study, can attest. Tumen speaks differently; Inner Mongolian dialect has a “j” sound where outer has a “ts” and the pronouns are a bit different. It’s a small city. He does not feel safe.

February 2008

Tumen has Tuya and me over for a real Inner Mongolian dinner, presenting a modest and bare but immaculately clean apartment on the worse side of town, near the black market. He gives me some kind of grain cereal at the bottom of a bowl of milky tea, then surprises me by thumbing off pieces of meat from the boiled sheep on the table and dropping them one by one into the bowl, something he keeps doing throughout the meal.

The second time I come by myself during the February holiday of tsagaan sar. He invited me weeks beforehand to be present on the first day of his wife and daughters’ ten-day visit. He and his daughter, Ona, a delicate university student with very good English, pick me up in a taxi (which in Ulaanbaatar is usually a regular guy in a regular car who could use a thousand tugriks or two). On the way up the stairs Tumen takes us one floor too far and then can't figure out why his key doesn’t work, and Ona gives him grief for it in universally understandable tones. The apartment is full and Tumen clearly happy, bickering with Ona, their voices zinging in Mongolian and Chinese across the kitchen. Tumen is immensely proud of his daughter, who tested into the top 10% of university students in China. I took videos of them singing traditional Inner Mongolian songs and smiled at his wife, a quiet geography teacher a few years older than Tumen, feeling guilty for knowing what was done to her at the border the last time she visited her husband, trying not to imagine it now that I had seen her tired face.

April 2008

It’s not spring by the standards of

my home in California—it snowed last

week—but it's sunny enough for

sunglasses as I wait for Tumen in

front of the State Department Store.

He approaches in a long black coat

and shades that make him look like a

spy in a big-budget movie. He smells

my cheeks, the customary Mongolian

greeting, and as we walk away from

the throngs, he says, “Min! United

Nations OK!” and gives a thumbs-up.

I whoop and call Och, who confirms.

Tumen is an official refugee,

eligible for resettlement. The

letter Larry Siems at PEN Freedom to

Write in New York sent expressing

concern about Tumen was crucial to

the decision.

To celebrate, Tumen takes me to a

Korean restaurant. He lays several

strips of fat with a bit of meat

attached (Mongolian meat always

comes this way) on the griddle set

up at our table. My Mongolian is

better than it was six months ago

when we met, but we still do a fair

amount of the gesturing. He’s keen

to know which presidential

candidates are leading in my

country, and overjoyed that Obama is

dark-skinned. He now wonders where I

think the best place to resettle

would be. America? He mimed an

injection into his arm, and then

reading a book, then put his arm

high into the air: hospitals and

university fees are high in America.

Resettlement can be a long and

difficult process. Canada or Europe,

we hope. He is very concerned that

Ona go to a good university. He

loves dogs, but can’t have one here.

Somewhere where he can have a dog.

Tumen insists that when I visit

Hohot next month I stay with his

wife. Sain okhin, he says,

kissing the top of my head. Good

girl.