|

|

|

Arja Rinpoche

|

|

|

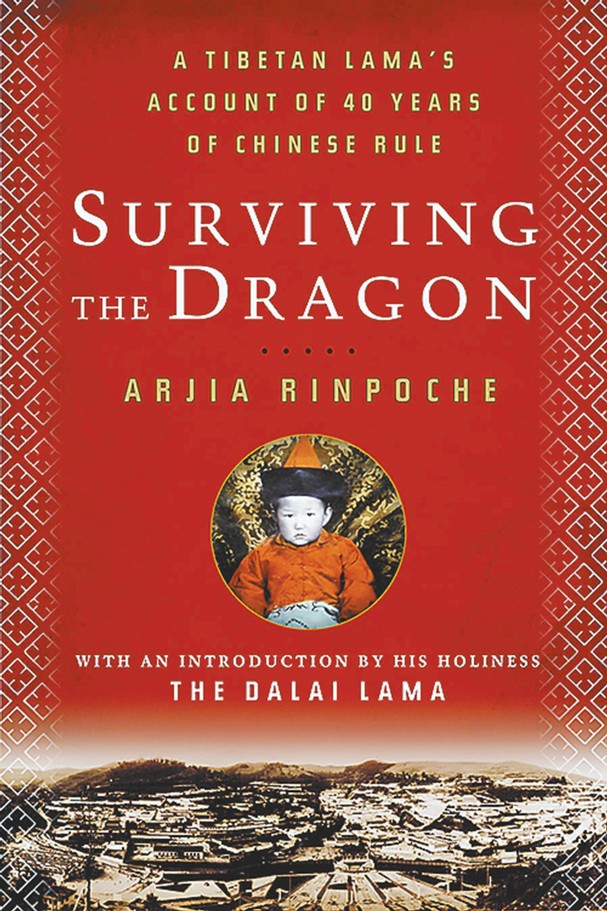

"Surviving the

Dragon" by Arjia

Rinpoche

|

Arjia Rinpoche former abbot of Kumbum Monastery in Tibet and founder of the Tibetan Center for Compassion and Wisdom in Mill Valley, Calif., will be in Knoxville Thursday and Friday, March 25 and 26. He will share the story of the turbulent years he spent in Tibet during the Cultural Revolution, including 16 in a forced labor camp.

At 6 p.m. Thursday, he will do a reading and book signing at Carpe Librum Booksellers, 5113 Kingston Pike Southwest.

At 3:30 p.m. Friday, a discussion will be held at the UT's University Center, rooms 223 and 224. At 7:30 p.m. the same day, a community forum will be held at Tennessee Valley Unitarian Universalist Church, 2931 Kingston Pike. All events are free and open to the public. Info: tvuuc.org and lslk.org

Rinpoche left Tibet in 1998 because of the repression of Tibetan culture and religion. He now lives in the United States. He is the only Tibetan high lama of Mongolian descent. He has trained with the Dalai Lama and the late Panchen Lama.

He regularly teaches and leads meditations at the Tibetan Center for Compassion and Wisdom in Mill Valley and in Oakland. In 2001, he spoke on behalf of the Tibetan people for the U.S. Commission on Religious Freedom.

He is the author of "Surviving the Dragon: A Tibetan Lama's Account of 40 Years of Chinese Rule" (Rodale Press).

Following is a Q&A with Rinpoche:

What is the Tibetan Center for Compassion and Wisdom?

TCCW is a sangha (congregation) that evolved very naturally where I first settled in the United States, in Mill Valley Calif. I had moved from New York, where I met the Dalai Lama and began my political exile, to Los Angeles, to a beach house on the Marin coast. For almost a year after my escape I felt as most immigrants must feel - alone and overwhelmed. Finally a generous soul offered me a beautiful old redwood house shaded on a two-acre peninsula of land shaped by an abundant stream. Although I was fearful and trying to maintain a low profile, two monks in maroon robes walking around a small town cannot remain inconspicuous for long. First one, then another and still another talked with me and asked if they could join our morning prayers. Soon we were too many people for morning prayers in what was our house, and we set a weekly schedule of teachings and prayers. It was a wonderful group, and they became my American family, and like a family we often prayed together, played together, studied together and ate together. That idyll lasted for eight years until His Holiness the Dalai Lama invited me to take charge of the Tibetan Mongolian Buddhist Cultural Center (TMBCC) in Bloomington Ind., which his older brother had founded but was too ill to manage.

How does a Tibetan monk like yourself react to American culture?

Of course in the beginning, it is very confusing. Many things are still confusing, but I have had good teachers, not just to learn English but to learn the ways and special qualities of Americans. I love many of the technical things we have here, especially my computer and my Photoshop. Most importantly, I found freedom to practice my religion as I had not been able to do since I was 8 years old. Also, I could never have written my memoir in China, let alone publish it. Not that I wanted to write an incendiary denunciation of the communist system in China; the pattern of my life was such a mirror of events in China in the second half of the 20th century that I felt I was a living record of that period - the ups and downs, the promises and disappointments.

As a recognized abbot, I lived a pampered life treated with loving care. In 1958 everything changed; the decade of benign neglect by Mao Zedong changed to rigid enforcement of communist ideology. Monks of good standing were arrested and tortured; monasteries were destroyed; privacy and private property was communized and I was sent to Chinese schools. Until 1962 Chairman Mao's policy called "the Great Leap Forward" led to famine all over Chinese-controlled land, including Tibet, and was followed by the infamous Cultural Revolution two years later. After Mao's death, I rose to a very high position within the religion and within the state, and still I felt forced to flee. All that was a story I had to tell!

What advice do you think most Americans most need to heed?

Americans, like most people in the world, need to remember and practice compassion, patience and understanding; they need to remember that hope rather than fear is the motivating source of happiness. America, I hear people sing, is the "home of the brave"; bravery is founded on hope, cowardice on fear. All religions say that. I hope my book can show how what seems to be suffering--and is--can be a strengthening force with the right help and vision. I am always grateful to my teachers for giving me that strength. Certainly American history and its traditions are teachers too. Compassion and harmony are the secret.

Following September 11, you organized a multidenominational day of prayer led by representatives of 10 different religions. What was most important to you about doing that?

The idea of such terror, horror and suffering for those who died, for their families and everyone else, in America and around the world united us, filled us with the guilt of what humans can do at their worst. Such suffering I understood from my own life. I wanted to share the prayers and practice that has always made such suffering bearable.