|

|

|

|

Contributor Andrew Clark

studied in Shanghai during the

spring of 2010. This is the

first in a series of stories

that touches on his political

and cultural awakenings

in-and-around China.

When Americans look at the world

map, China seems to be a unified

block of land. In reality, China

is made up of several unique

ethnic groups that are having

trouble assimilating to unified

rule.

During my last week in China, a

friend and I took one final trip

to one of the most exotic,

off-the-map places in

China -- Hohhot, in

Inner Mongolia. Hohhot is

situated in northern China, near

the border of Mongolia, and is

the ancestral home of the Mongol

people (think

Genghis Kahn and his nomadic

hordes). Signs in the region are

in both Chinese and Mongolian,

and many of the locals can speak

both languages with ease. The

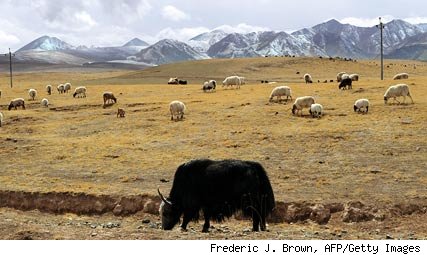

terrain of the area is uniquely

marked by both endless

grasslands, where herds of sheep

and cows graze, and sprawling

sand dune deserts abound --

reminiscent of the African

Sahara.

I took an excursion one morning

out to the Xilamuren Grasslands,

two hours north of Hohhot, where

I was invited to spend a night

in a local

family's

yurt. At one point during

our lunch, I asked our tour

guide, a local

ethnic Mongolian: What exactly

is an autonomous region? After

all, China is otherwise made up

of provinces, what's the

difference?

"Because we Mongolians are an

ethnic minority, and not Han

Chinese (the predominant

ethnicity of China), the

government gives us special

rights and control over our

region," she responded. Through

her accent, however, I noticed a

sense of sarcasm.

"So that's a good thing, right?"

I asked.

"No, not really," she replied,

then explained why.

Han Chinese make up 92 percent

of the People's Republic of

China. The remaining 8 percent

is made up of minority groups,

mainly Tibetan, Zhuang, Uyghur,

Mongolian, Miao, Manchu, and Hui

(these are the major ethnic

groups -- China officially

recognizes 55 minority

populations). Each of these

minority groups are native to

land within China's borders

(mainly in the West and the

North), and three of them

(Tibetan, Uyghur, and Mongolian)

live in autonomous regions. The

ancestral land of these

minorities makes up about half

of modern-day China, yet their

ethnicities make up only a tiny

fraction of the modern-day total

population.

As one can imagine, this often

leads to ethnic tension. The

Chinese government acknowledges

the awkwardness of the Han

ruling a nation in which half

the territory does not identify

with the majority. So, in an

attempt to release some of that

tension, they've given these

ethnicities autonomous rule. As

our Mongolian guide explained to

me, though, this is only

satisfying on the surface.

In reality, while autonomous

rule allows for the local

minority to choose their own

regional governor, and have more

legislative rights, the Chinese

Communist Party (CCP) still

appoints its own regional Party

Secretary -- in China, the

communist positions are where

the real power is located. The

current Party Chief of Inner

Mongolia is Hu Chunhua, and

while he is seen as a star among

a new

generation of rising Chinese

leaders, he is still ethnic Han

Chinese.

Further, the CCP still controls

the public education system,

which is often the front-lines

in battles for control of the

future. Class in Inner Mongolia,

regardless of location, is

taught in Chinese, and there is

little encouragement of young

students to study or learn their

family's traditional language.

Indeed, in the Mongol yurt I

visited, which consisted of a

mother, father, and a teenage

daughter, the daughter was

unable to speak a word of

Mongolian (her parents spoke it

fluently), so the family

conversed in Chinese. My tour

guide told me that, among the

Mongolians, there is a real

sense that the Han Chinese are

trying to, quietly, stamp out

Mongolian culture. (After an

unusual arrest last year,

the leader of the Inner

Mongolian People's Party, Xi

Haiming, claimed that, "the

Chinese Communist Party wants to

divide and rule . . . their

purpose is hidden but its the

eradication of Tibetan and

Mongolian culture.")

This, of course, may be somewhat

exaggerated, but nonetheless,

the tension is there. The

sentiment is not restricted to

just Inner Mongolia, and it is

not all peaceful. You may

remember the

high-profile conflict in

Tibet in the months leading to

the 2008 Olympic Games, as angry

Buddhist monks and other ethnic

Tibetans rose up against the

ruling CCP. Similar

unrest happened last summer

in Xinjiang province among the

Uyghurs, where 156 were killed,

800 injured, and more than 1,000

detained. In 2004, unrest

broke out among the Hui in

Henan province. That incident

was particularly startling, as

what triggered the outbreak was

a quarrel between a Hui tax

driver who (allegedly) ran over

a Han girl.

China is one of the oldest

and richest cradles of

civilization in the world, and

much like the Middle East,

multiple ethnic groups call upon

ancient traditions to claim

land, autonomy, and sovereignty

-- or at least more acceptance

and representation by a majority

that seems to be uninterested in

all of the above.

However, the Han likewise seem

to have no desire to give up

these lands. Chinese history is

pockmarked with invasions and

internal rebellion, breaking up

unified Chinese empires. The Han

Dynasty unified China in 206 BC

and ruled over a golden age,

only to have the

Three Kingdoms Era lead to

bloody civil war and economic

disaster; subsequent Mongol

invasions, and then Western

intervention, has led the

Chinese to believe that a

unified China is in the best

interest of everyone, and

division can only lead to

crippling.

It remains to be seen whether

the Chinese government can

successfully assimilate these

groups, or if consistent

suppression of uprisings can

force social tranquility. While

on the margins, some scholars

even believe that China will

fall apart (one Chinese expert,

Gordon Chang, labeled China's

current minority-policy "unsustainable").

Nevertheless, while the United

States has seemingly countless

ethnic and cultural minorities

that are proud to call

themselves American, the same

cannot be said for China. "I am

not Chinese," our tour guide, a

Chinese-citizen, told me. "I am

Mongolian." If China hopes to

continue to rise as a growing

world power, and keep its

government stable, these

attitudes will surely need to be

addressed. Otherwise, the

government may have a hard time

moving forward when so much of

their resources are spent on

suppressing ethnic dissent.

Filed Under: The Cram

Tagged: autonomous areas of china, ccp, china, han chinese, Inner Mongolia, Mongolia