|

|

|

|

BEIJING — A prominent ethnic Mongolian dissident imprisoned in China on charges of espionage and “separatism” was released last week when his 15-year term was up, but he remains missing along with his son and wife, according to human rights groups.

The dissident, Hada, 55, who like many Mongolians uses a single name, is an influential advocate for Mongolian culture and one of China’s longest serving political prisoners. A writer and former bookstore owner, he has long sought greater autonomy for ethnic Mongolians, most of whom live in Inner Mongolia, a vast province of grassland and desert that stretches more than halfway across the northern reaches of China.

Although Inner Mongolia is now 80 percent Han Chinese, the result of 60 years of migration that has essentially flipped its ethnic composition, the province’s four million Mongolians have struggled to maintain their linguistic and cultural identity, one shared by those living in Mongolia, the independent nation to the north.

Their quest for greater freedom has been overshadowed by the more publicized efforts of Tibetans and Uighurs, two other minority groups in China whose numbers have been overwhelmed by Han migration and whose efforts to maintain — or reclaim — religious, cultural and linguistic autonomy have led to violent clashes with the Chinese.

Mr. Hada was arrested in 1995 after organizing a rally in the provincial capital, Hohhot, that drew dozens of people, according to foreign newspaper accounts at the time. After his detention, about 200 college students gathered outside his bookstore to sing Mongolian songs and hold up pictures of the Mongol conqueror Genghis Khan.

Mr. Hada’s conviction, announced a year later, was based on his role as a founder of the underground Southern Mongolian Democracy Alliance, a group that seeks independence for the region. The espionage charges stemmed from interviews he gave to Voice of America and overseas news media.

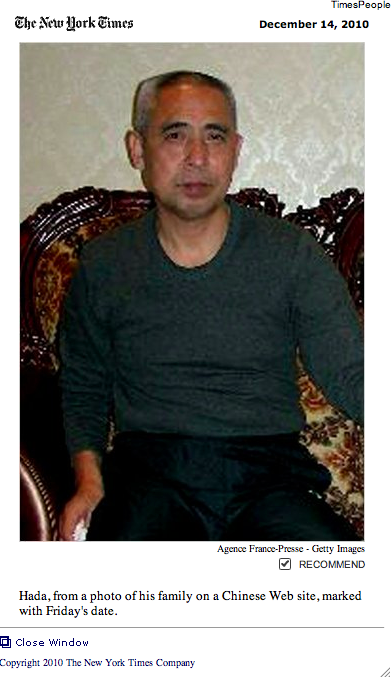

According to the Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center in New York, Mr. Hada’s wife and son have not been heard from since they were detained by public security agents this month. On Saturday, a day after Mr. Hada’s scheduled release, photographs of the family were anonymously posted on a Chinese Web site, stamped with Friday’s date and labeled “family reunion.” According to the group, the police delivered a DVD with the same pictures — which show the family smiling over a table overflowing with food — to a relative later that day.

“This is illegal and unlawful, because according to Chinese law, Hada should be totally free after Dec. 10,” said Enghebatu Togochog, the information center’s director. “Not only are they not freeing him, but they are detaining his family members too.”

A call to the Public Security Bureau in Chifeng, the city where Mr. Hada was imprisoned, was referred the No. 4 Detention Center. There, a man identifying himself as a prison employee hung up when asked about Mr. Hada’s whereabouts.

The continued detention has stirred concern among human rights advocates, who say Chinese authorities are increasingly inclined to use extralegal measures to rein in and punish opponents. Gao Zhisheng, a well-known Beijing lawyer who says he was tortured by the police during a previous detention, has been missing for months. Another rights advocate who exposed coerced sterilizations, Chen Guangcheng, has been confined since September to his home in rural Shandong Province with his family despite having served more than four years on a conviction for damaging property.

Joshua Rosenzweig, a Hong Kong-based researcher at nonprofit Dui Hua Foundation, which promotes Chinese-American dialogue on human rights, said Mr. Hada’s long sentence and the fact that it was not reduced for good behavior highlights Beijing’s hard line toward those who support separatist aspirations among the country’s ethnic minorities. Over the past 15 years, he said his organization and other rights groups repeatedly pressed Mr. Hada’s case with top Chinese officials.

“It seems that ethnic minority prisoners face an even harder time than ordinary prisoners getting clemency,” he said. “Even individuals imprisoned for crimes like rape and robbery get time off for good behavior.”

Mr. Togochog of the New York-based information center described Mr. Hada as a “hero of the Mongolian people” who refused a recent offer by the Chinese authorities: go into exile or stay in China and keep his mouth shut.

In exchange, the police said they would arrange a well-paid job and a home, according to Mr. Togochog, who had been in frequent contact with Mr. Hada’s wife and son before they disappeared. Mr. Togochog said that Mr. Hada refused either option and vowed to sue the police for his years of detention.

“He is very determined,” Mr. Togochog said.

Zhang Jing contributed research.